Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) Public domain photo.

Objectives

- Demonstrate the ability to educate clients about control options.

- Provide a diagram of typical sets used to capture squirrels.

- Identify various risks involved with homes infested with squirrels.

Legal Status in New York

Gray and fox squirrels are protected game species, with set seasons (the “black” squirrel is actually a gray squirrel that’s just darker). Red and flying squirrels are unprotected.

NWCOs may take or possess gray, fox, red, or flying squirrels without any additional permit from the DEC when the animal is damaging or destroying property or found to be a nuisance.

Overview of Damage Prevention and Control Methods

Habitat Modification

- Remove bird feeders

- Cut down or trim trees back at least 6 feet from buildings

Exclusion

- Install sheet metal bands on isolated trees to prevent damage to developing nuts

- Install chimney caps and seal any gaps in the chimney flashing

- Close external openings to buildings; do not seal animals inside the home

- Plastic tubes on non-electrical service wires may prevent access to buildings

Frightening Devices

- Strobe lights

Repellents and Toxicants

In New York, any use of toxicants or repellents by NWCOs requires the NWCO to have a pesticide applicator license.

Shooting

- .177-caliber pellet guns

- .22-caliber rifles

- Shotguns with No. 6 shot

Trapping

- 5- x 5- x 18-inch (minimum) cage or box traps

- Rat traps, tunnel traps, or body-gripping-style traps depending on species

Other Control Methods

Squirrel Species Information

Identification

- Fox squirrel (Sciurus niger)

- Eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)

- Red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus)

- Southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans)

- Northern flying squirrel

(Glaucomys sabrinus)

Physical Description

In this module, tree squirrels are divided into 3 groups: large tree squirrels (fox and gray squirrels), pine squirrels (red squirrels), and flying squirrels. Eastern gray squirrels typically are gray, but have some variation in color. Some animals have a distinct reddish cast to their gray coat. Black individuals are common in some areas. Local populations of white gray squirrels are found in upstate New York. Though not albino, white squirrels have gray on the back of their heads, necks, or shoulders. Several color variations can occur in a single population.

Fox squirrels are larger than eastern gray squirrels. They can vary in color from a deep orange-rust color to a more reddish color with yellow undersides.

Red squirrels are red-brown above with white under parts. They have small ear tufts and often have a black stripe separating the dark upper color from the light belly.

Two species of flying squirrels occur in New York, and it can be difficult to distinguish them. Both may be various shades of gray or brown above and lighter below. A sharp line of demarcation separates the darker upper body from the lighter belly. Typically, the northern flying squirrel is reddish-brown and the southern flying squirrel is more of a gray color. Flying squirrels do not actually fly, but rather glide. The most distinctive characteristics of flying squirrels are the broad webs of skin connecting the fore and hind legs at the wrists (to aid in gliding), large black eyes, and the distinctly flattened tail.

Large tree squirrels include fox squirrels that measure 18 to 27 inches from nose to tip of tail. They weigh about 1¾ to 2¼ pounds. Eastern gray squirrels (Figure 1) measure 16 to 20 inches. They weigh 1¼ to 1¾ pounds. Red squirrels are considerably smaller. They are 10 to 15 inches long and weigh 1/3 to 2/3 pounds. Southern flying squirrels are 8 to 10 inches long and weigh 1½ -2 ½ ounces. Northern flying squirrels average 10 to 12 inches, and weigh 2.6 to 4.4 ounces.

Voice and Sounds

Squirrels emit a variety of sounds including churrs, barks, and squeals. Churrs express anger, barks act as warnings, and squeals occur when a squirrel is terrorized or in pain.

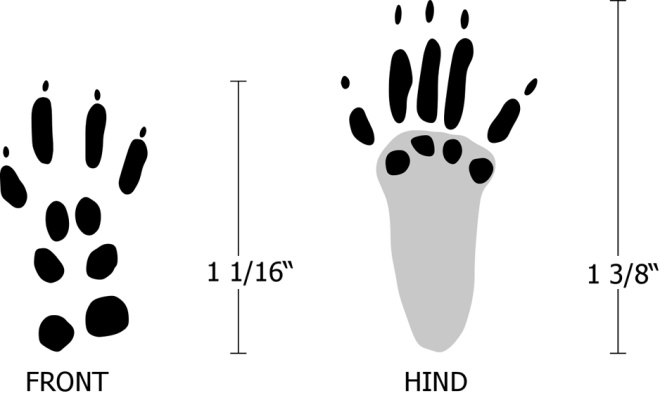

Tracks and Signs

General Biology

Reproduction

Fox and gray squirrels first breed when they are about a year old. Gray squirrels breed in mid-December or early January, and a small percentage breeds again in June. Fox squirrels breed in January. Young squirrels may breed only once in their first year. The gestation period is 40 to 45 days with young born in February-March. During the breeding season, noisy mating chases take place when 1 or more males pursue a female through the trees. Tree squirrels have about 3 young per litter. At birth, they are hairless, blind, and their ears are closed. Young weigh about ½ ounce at birth and 3 to 4 ounces at 5 weeks. At weaning they are about half of their adult weight. Young begin to explore outside the nest about the time they are weaned at 10 to 12 weeks. After the young are weaned, they usually do not remain with their parents. However, young female gray squirrels may stay with their mother for several months, although they don’t necessarily remain near the nest site.

Typically, about half of the squirrels in a population die each year. In the wild, squirrels over 4 years old are rare, while individuals may live 10 years in captivity.

Red squirrels breed in late winter and the gestation period is the same as gray and fox squirrels. The litter size is 3 to 6 young.

Northern flying squirrels breed in late winter and southern flying squirrels in early spring. They produce 2 to 7 young. Flying squirrels are active at night. All other species are active primarily during the day.

Nesting/Denning Cover

Squirrels are cavity dwellers, preferring hollow trees and buildings . Large leafy nests, called dreys, are constructed with a frame of sticks filled with dry leaves and lined with leaves, strips of bark, corn husks, or other materials, are constructed particularly in the summer, as they are cooler. Squirrels will also den in rock crevices, burrows, brush piles, chimney flues, attics and barns. Survival of young in cavities is higher than in leaf nests, making cavities preferred sites for nests.

Red and flying squirrels prefer old woodpecker nest holes and hollow tree limbs.

Photo by Stephen M. Vantassel.

Behavior

Individual home ranges vary from 1 to 100 acres, depending on the season and availability of food. Squirrels move within their range according to the availability of food. They often seek mast-bearing forests and corn fields in the fall and tender buds of maple trees are favored in the spring. During fall, squirrels may travel 50 miles or more in search of better habitat. Populations of squirrels fluctuate regularly. When population numbers are high, squirrels, especially gray squirrels, may go on mass emigrations where many individuals die.

Habitat

Gray squirrels are the most common and adaptable squirrel species. They can inhabit just about any habitat and are often found in great numbers in cities, especially in and around parks. The fox squirrel has the most limited distribution of all the squirrels in NY. They are found only in pockets in the most western part of the state. The presence of mature hardwoods often is important to all the species of squirrels. Flying squirrels, being more arboreal (tree-dwelling), are restricted to areas of large, mature hardwoods or mixed forests. Gray and fox squirrels prefer hardwood forests (fox squirrels like the forest edge); red squirrels prefer softwood forests or mixed hardwoods and conifers; flying squirrels also prefer mixed forests, but aren’t as picky as red squirrels.

Food Habits

It is important to distinguish the types of food storage used by squirrels. Large squirrels, such as gray and fox squirrels, scatter cache, which means they store individual acorns or other seeds (mast) in different areas around their home range. Smaller squirrels, such as red squirrels, store food in 1 place. It is not uncommon to find trash-bag-sized piles of pine cones inside attics or gutters, brought there by red squirrels.

Fox and gray squirrels have similar food habits. They eat a variety of native foods and adapt quickly to unusual sources of food. Typically, they feed on mast (wild tree fruits and nuts) in fall and early winter. Acorns, hickory nuts and walnuts are favorite fall foods. Fox squirrels feed heavily on pine cones; gray squirrels will as well in spring. Nuts often are cached for later use. In late winter and early spring, both species prefer tree buds. In summer, they eat fruits, berries, and succulent plant materials. Fungi, corn, and cultivated fruits are taken when available. Squirrels chew bark from a variety of trees.

The food habits of flying squirrels generally are similar to those of other squirrels, though they are the most carnivorous of all tree squirrels. They eat bird eggs and nestlings, insects, and other animal matter when available. Flying squirrels often occupy bird houses.

Damage Identification

Damage to Structures

Squirrels, being rodents, are known for their gnawing. The size of holes made by squirrels can be generalized. Fox and gray squirrels use holes the size of a baseball. Red squirrels use holes the size of a golf ball. Flying squirrels use holes the size of a quarter.

Squirrels often travel power lines and short out transformers. They gnaw on wires, enter buildings, and build nests in attics. They may chew holes through tubing used in maple syrup production. Feces of flying squirrels mixed with urine can cause stains.

Photo by Stephen M. Vantassel.

Damage to Livestock and Pets

Squirrels do not pose a threat to pets, but will consume bird eggs and nestlings. Flying squirrels are small enough to enter most bird houses and are likely to eat nestling birds.

Damage to Landscapes

Squirrels occasionally damage trees by chewing and stripping bark from branches and trunks. Red squirrels damage pine trees and paper birch.

Tree squirrels may eat pine cones and nip twigs to the extent that they interfere with natural reseeding of important forest trees. In forest seed orchards, squirrel damage interferes with commercial seed production.

In nut orchards, squirrels can severely curtail production by eating nuts prematurely and by carrying off mature nuts. In fruit orchards, squirrels may eat cherry blossoms and destroy ripe pears. Red, gray, and fox squirrels may chew the bark of various orchard trees.

Squirrels may damage lawns by burying or digging up nuts. They chew bark and clip twigs on ornamental trees or shrubbery planted in yards. Squirrels often take food at feeders intended for birds. Sometimes they chew to enlarge openings of bird houses and then enter to eat nestling songbirds. Squirrels may eat planted seeds, mature fruits, corn, and grains.

Health and Safety Concerns

Squirrels chew on electrical lines, leading to fires. If left long enough, their gnawing can weaken rafters.

Fox and gray squirrels are vulnerable to several parasites and diseases. Ticks, mange, fleas, and internal parasites are common. Squirrel hunters often notice bot fly larvae, called “wolves” or “warbles,” protruding from the skin, especially before frosts. The larvae do not impair the quality of the meat for eating and they are not known for harboring diseases dangerous to humans. The droppings of flying squirrels have been associated with murine typhus.

Damage Prevention and

Control Methods

Squirrels are active year-round and can be controlled whenever they are causing damage. Care must be taken to avoid abandoning young during the period when young maybe present, which can be February through August, as some species may mate twice a year.

In situations with longstanding conflicts with tree squirrels, it is wise to use a variety of cost-effective methods to control the damage. Squirrels cause economic losses to homeowners, nut growers, and forest managers but the extent of these losses is not well known.

Squirrels occasionally chew on electrical wires associated with vehicles leading to replacement costs of $500 to $1,000. Squirrels caused 177 power outages (24% of all outages) in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1980. Estimated annual costs were $61,005 (2010 prices) for repairs, public relations, and lost revenue. Squirrels caused 332 outages in Omaha, in 1985, costing at least $94,237 (2010 prices). After squirrel guards were installed over pole-mounted transformers in Lincoln in 1985, annual costs were reduced 78% to $10,290 (2010 prices).

Habitat Modification

Trim limbs and trees to 6 to 8 feet away from buildings to prevent squirrels from jumping onto roofs. Other plants, such as ivy, that allow access should be trimmed as well. In backyards where squirrels cause problems at bird feeders, consider providing an alternative source of food. Wire or nail an ear of corn to a tree or wooden fence post away from where the squirrels are causing problems. Bird feeders should be modified to prevent foraging by squirrels at the feeder itself and on the ground. In high-value crop situations, it may be beneficial to remove woods or other trees near orchards to block the “squirrel highway.”

Exclusion

Prevent squirrels from traveling on wires by installing 2-foot sections of lightweight 2- to 3-inch diameter plastic pipe. Slit the pipe lengthwise, spread it open, and place it over the wire. The pipe will rotate on the wire and cause traveling squirrels to tumble. Critter Guard® (Critterguard.org) has created a device to stop squirrels from crossing wires. NEVER install wire guards on or near electrical bearing lines. Only professional electricians and power company employees should handle power lines.

Prevent squirrels from climbing isolated trees and power poles by encircling them with a 2-foot wide collar of metal 6 feet off the ground. Consult the local power company before installing anything on a power pole.

Attach metal using encircling wires held together with springs to allow for growth of the tree. Close openings to attics and other parts of buildings but make sure not to trap squirrels inside. They may cause a great deal of damage in their efforts to chew out.

Place newspaper in a hole to determine if squirrels are actively using it. Place traps inside as a precaution after openings are closed.

A squirrel excluder can be improvised by mounting an 18-inch section of 4-inch plastic pipe over an opening. The pipe should point down at a 45° angle.

When young are present, remove the entire family before blocking the entrance to their den. If the young are older and mobile, install a 1-way door over the entry hole. They will leave but won’t be able to re-enter. Make a squirrel excluder as described above. If the squirrels are caught in a chimney, give them a way to climb out. Place a small weight on a rope that is 1” in diameter. Drop the rope down the chimney. The weight helps you drop the rope all the way down, and then keeps the rope taut so the squirrels can climb it (check additional information in the ‘Squirrels in Chimneys and Basements’ section). Once the squirrels have left, cap the chimney so they won’t enter it again.

Trap and release strategies to reduce the risk of orphaning wildlife:

The best way to prevent orphaning is to convince your customers to wait until the young are mobile before removing, repelling, or excluding the family from the site. If that is unacceptable, you can try to capture and remove both the female and all of its young and hope that it will retrieve them and continue to care for them.

Place the female and young in a release box. Many NWCOs use a simple cardboard box, others use a wooden nest box, such as a wood duck box, and some prefer plastic boxes. Match the size of the box and its entrance hole to the size of the species (try a 2x2x1 ft. box). Make sure the animal cannot immediately get out of the box by covering the hole. Then move them a quiet place outdoors. Unless they are likely to be disturbed, keep the box at ground level. Remove the cover so the female can get out of the box. Another option is to build a box with a sliding door. Leave the door open about an inch to keep the heat inside, but make it easy for the female to slide it fully open so it can retrieve its young. If you can’t catch the female, put the young in the heated box and locate it as close to the entry site as possible, or put them in a nearby tree. The female may continue to care for the young, or she may abandon them. Check the next day to see if the young are still there. If so, they have probably been abandoned. This technique may be more effective with older, more experienced females.

When young are not of concern, 1-way doors can be an effective tool. Use spring-loaded 1-way doors in combination with a large (1-foot square minimum) apron around the hole to reduce chew-ins. Freezing rain can freeze the door shut or open. Some animals will fight to enter harder than others to gain access. Chew-ins may occur, so prepare customers for the possibility. Flying and red squirrels are easier to exclude because they lack the jaw strength of larger squirrels. Effective squirrel eviction requires careful site evaluation. One-way doors work best when the structure is sound, as this reduces the likelihood that a squirrel will chew in elsewhere. Secure vents and chimneys before installing a 1-way door.

Some NWCOs use 1-way doors in combination with traps to help finish the job more quickly, as it motivates squirrels to check out the traps. Some 1-way doors are attached to traps turning them into what is known as “positive trapping.”

Close openings to buildings with heavy ½-inch wire mesh, aluminum flashing, or make other suitable repairs. Custom-designed wire-mesh fences topped with electrified wires may keep squirrels out of gardens or small orchards.

Frightening Devices

No frightening devices have been proven effective. Strobe lights show some promise.

Repellents and Toxicants

In New York, any use of toxicants or repellents by NWCOs requires the NWCO to have a pesticide applicator license.

Before using any product, you must check the New York State Pesticide Administrator Database (NYSPAD) to see if the product is registered for use in NY and for the target species. For example, if the product is registered for use on squirrels, it cannot be used for deer. The following are presented as examples of repellents and toxicants that may be effective.

Repellents

Naphthalene may temporarily discourage squirrels from entering attics and other enclosed spaces. Use of naphthalene in attics of occupied buildings is not recommended, however, because it can cause severe distress to people. Use of any commercial repellent may require certification for pesticide use.

Ro-pel® is a taste repellent that can be applied to seeds, bulbs, flowers, trees, shrubs, poles, fences, siding, and outdoor furniture. Another taste repellent, capsaicin is registered for use on maple sap collecting equipment.

Polybutenes are sticky materials that can be applied to buildings, railings, downspouts, and other areas to keep squirrels from climbing. Polybutenes can be messy. A pre-application of masking tape is recommended. These products are best used to stop gnawing damage.

Toxicants

No toxicants are registered for the control of tree squirrels.

Shooting

Where firearms are permitted, shooting is effective. A shotgun, an air rifle or a .22-caliber rifle is suitable. Pellet rifles (.177-caliber) are another option.

Trapping

The biggest trapping errors committed in the control of squirrels are:

- failure to use enough traps

- over-reliance on bait

- improper location

- use of the wrong traps

Several rules apply for trapping tree squirrels. First, place traps near den holes or on travel routes. Do not rely on bait to overcome poor location of traps. Most traps will be located off the ground, so be sure they are secure. Use enough traps and the correct type of traps. For gray and fox squirrels, use at least 3 traps; for red squirrels use 5 or more; use several more when trapping flying squirrels. Remove competing sources of food.

Cage Traps

Cage and box traps sized 5 x 5 x 18 inches or larger are effective in capturing tree squirrels. Use of cages made from ½- x 1-inch mesh will reduce the likelihood of damage to surrounding materials by trapped animals. Cage traps can be secured to trees and plywood shelves. In each case, be sure the squirrel has a 2- to 3-inch area to stand in front of the door. Multiple-capture cage traps are available for use on flying squirrels, and can be used on other squirrels as well (Figure 9). Place food in the trap as this may reduce their stress and the risk that the animals will fight.

Body-gripping Traps

Body-gripping traps are very effective and show a low refusal (avoidance) rate, as they are quite inconspicuous. These traps are most commonly used in a positive set, in which the trap is set over the only entry available. Tunnel traps offer an excellent way to catch squirrels as captures are almost completely out of public view. Drill small holes at the ends of the trap to enable you to secure the trap several ways.

Two tunnel traps secured to a sheet of plywood to protect the roof. Photo by Stephen M. Vantassel.Effective bait for squirrels includes slices of orange and apple, walnuts or pecans removed from the shell, and peanut butter. Other foods, such as corn or oil-sunflower seeds that are familiar to the squirrel also may work well. Nuts rarely work as bait during fall when natural foods are available. Consider alternate baits if trapping in fall.

Rat-sized snap traps are very effective on red and flying squirrels. Place them inside cubby boxes to force squirrels to approach the trigger only, or set them vertically on walls with bait side down. Use these traps indoors or where birds cannot access them.

Foothold Traps

Foothold traps are not recommended, due to risks to non-target animals and concerns about humanness.

Disposition

On-site Release

In rescue situations such as from chimneys or basements, on-site release of squirrels is recommended, provided the entrance has been secured.

Relocation and Translocation

Tree squirrels should not be moved a great distance because of the stress placed on both transported and resident squirrels, and concerns regarding the transmission of diseases. NWCOs must have the permission of the landowner where the animal will be released.

Euthanasia

Carbon dioxide is the preferred method of euthanasia for tree squirrels. Squirrels expire relatively quickly in a carbon-dioxide rich environment.

Disposal

Check state and local regulations regarding disposal of carcasses.

Other Control Methods

Squirrels in Chimneys and Basements

During the mating season, it is not uncommon for males to search openings, looking for females. Unfortunately, many squirrels become trapped in chimneys, as they are unable to grip the smooth flue tiles. Removal of squirrels in chimneys is a special circumstance fraught with risk. The largest risk is being bitten when handling squirrels. In addition, there is a chance that a soot-covered squirrel will run around a pristine living room. Several different chimney types and situations exist, so we provide a few principles to help guide your work with squirrels in chimneys. Before opening a chimney damper, wear your personal protection equipment (PPE) including a hat or cap, safety glasses, a dust mask, and heavy gloves.

A squirrel trapped in a chimney rarely will survive for more than 3 days. It is normal for the noise level to drop as a squirrel weakens. Try to remove squirrels before they die in a chimney.

If possible, secure the opening of a fireplace, set a baited trap, and open the damper. Return the next day. Squirrels may be able to climb out if a 1-inch thick hemp rope is hung in the flue. Squirrels must be healthy enough to climb for this to be an effective technique. Use snake tongs to grab squirrels that are cornered, and hand nets to catch loose squirrels. Before opening a damper, remove valuable and breakable items, and close doors in the vicinity. Squirrels will run to daylight, so try to make the lighted area lead to the outdoors.

Acknowledgments

Authors

Material is updated and adapted from the book, Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage, 1994, published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension.