- Learning Objectives

- Terms to Know

- Introduction

- Safety Tips to Share with Your Customers

- Agents of Disease Transmission

- Common Zoonotic Diseases

- Diseases, Based on Transmission

- Fecal-Oral Transmission

- Preventing Fecal-Oral Transmission

- Respiratory Transmission

- Preventing Respiratory Transmission

- Direct Contact Transmission

- Preventing Direct Contact Disease Transmission

- Penetrating Wound Transmission

- Preventing Penetrating Wound Transmission

- Vector-borne Diseases

- The Bottom Line Regarding Diseases

- Acknowledgments

- Study Questions for Wildlife Diseases

Learning Objectives

- List the most common zoonotic diseases.

- Describe the groups (humans, pets, wildlife) most vulnerable to disease transmission.

- Explain the need for protective equipment and why people should wear it.

- Explain the causes of the most common zoonotic diseases.

- List 5 common ways that zoonotic diseases are transmitted to humans.

Terms to Know

Agent An organism or entity that causes disease.

Host An organism negatively affected by the disease.

Reservoir An organism that harbors or carries the disease but is not harmed by the disease.

Vector The route of infection (typically an organism).

Zoonotic Diseases originating from wildlife that can be transmitted to humans.

Introduction

The module on wildlife diseases provides basic information on zoonotic diseases, specifically those that wildlife may transmit to humans. Wildlife can carry many diseases. All WCOs need to be aware of the dangers of wildlife diseases, as well as how to avoid becoming infected and spreading diseases to other people or animals.

Zoonotic diseases, or zoonoses, are infections that wildlife can pass to people through either direct contact (bites, scratches, ingestion) or indirect means (mosquitoes, ticks, contact with infected urine or feces, contamination). About 200 zoonotic diseases are known at this time. Unfortunately, biological hazards encountered in nature do not come with warning signs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Universal warning sign for a biological hazard. Wildlife have bio-hazards that are not easy to see.

Image from Safety Image CD.

Some wildlife diseases can be fatal to people, although injuries associated with ladders and roofs are far more common for WCOs than catching a wildlife disease. Even if you are comfortable with your personal risk, you owe it to your customers to be cautious.

Diseases can be spread from one population of wildlife to another, with potentially devastating effects. For example, white-nose syndrome is killing bats across the eastern US and people can facilitate transmission. Rabies vector species like skunks and raccoons should not be translocated. Translocating deer can spread chronic wasting disease (CWD).

As a professional, you are expected to behave in ways that minimize the risk of exposing other wildlife, humans, and domestic animals to diseases and help prevent the spread of diseases to other areas or species. Zoonotic diseases influence procedures for animal handling and disposal, choice of gear, customer education, and clean-up strategies for the site and your equipment.

Safety Tips to Share

with Your Customers

Teach children never to handle unfamiliar animals, wild or domestic, even if they appear friendly. “Love your own, leave other animals alone.”

Enjoy wildlife from afar. Never adopt wild animals or bring them into your home. Do not handle, feed, or unintentionally attract wild animals to your home or yard.

Do not try to rescue baby birds or other baby animals. They usually don’t need it. Do not try to nurse a sick animal back to health. Go online or contact a wildlife rehabilitator or state wildlife staff if you have questions.

How much do you need to know about wildlife diseases? You’re not a doctor, after all, but you do need to know enough to protect yourself and others, and to answer your customers’ questions. Sometimes our fears about wildlife diseases are much greater than our actual risks of catching them. It can be tricky to share the necessary information with a customer in the right context. Do not try to sell a job by frightening customers with an overblown assessment of the risk of catching a wildlife disease.

It also is important to resist jumping to conclusions. For example, distemper can cause symptoms that look like rabies. The only way to be sure is to have the sick animal tested.

Some of wildlife diseases can be fatal. That’s something your customer will probably want to know — what’s the worst-case scenario? The chance of catching most of these diseases is low, and even then, many of them are treatable.

The trick is to have good, complete, and credible information from a trusted source. One extremely valuable source for current and accurate information is the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Most of the pages on their website (www.cdc.gov) about wildlife-related health issues are written in simple language and get right to the point.

One last point: when you remove wildlife from people’s homes, plan for the parasites that may be left behind. Birds and mammals are host to a variety of parasites including fleas, ticks, mites, and lice. Although these parasites generally prefer their original host species, if you remove those animals, the hungry parasites may enter the home looking for a meal. Many of these parasites will bite people and they can be extremely annoying. Itchy customers generally are not happy, which isn’t good for business.

Agents of Disease Transmission

Awareness of how humans are infected by diseases will help you take precautions to prevent exposure to disease agents.

Disease agents (pathogens):

- bacteria,

- viruses,

- protozoans (single-celled organisms),

- rickettsia (microorganisms that combine aspects of both bacteria and viruses),

- fungi,

- nematodes (multi-celled worms), and

- prions (modified proteins).

Agents can enter your body through:

- injection by a tick or wildlife bite,

- ingestion (biting contaminated fingernails, eating contaminated food),

- inhalation (breathing contaminated dust or airborne eggs), and

- absorption (organism enters through mucosal membranes around the eyes and mouth, or through a break in the skin).

It also is important to resist jumping to conclusions. For example, distemper can cause symptoms that look like rabies. The only way to be sure is to test.

Some of wildlife diseases can be fatal. That’s something your customer will probably want to know—what’s the worst-case scenario? The chance of catching most of these diseases is low, and even then, many of them are treatable.

The trick is to have good, complete, and credible information from a trusted source. One extremely valuable source for current and accurate information is the CDC. Most of the pages on their website about wildlife-related health issues are written in simple language and get right to the point.

One last point: when you remove wildlife from people’s homes, it is important to plan for the parasites that may be left behind. Birds and mammals are host to a variety of parasites including fleas, ticks, mites, lice, and bugs. Although these parasites generally prefer their original host species, if you remove those animals, the hungry parasites may enter the home looking for a meal. Many of these parasites will bite people and they can be extremely annoying. Itchy customers generally are not happy, which isn’t good for business.

Figure 2. Deer ticks (male left; female center pre-feeding; and right post-feeding) are capable of transmitting the agent of Lyme and other diseases.

For example, Lyme disease has a bacterial agent. Ticks (Figure 2) are the vectors that infect humans (the host) when they bite. Deer mice are a reservoir species that become carriers of the disease agents.

Protect your health by understanding how wildlife diseases are transmitted to humans, the symptoms they cause, and how to avoid exposure. The protective equipment mentioned in Module 2 is helpful to prevent exposure to disease agents. The following table gives information on how people contract various zoonotic diseases, and precautions a WCO should take to help reduce the risk of contracting or transmitting one.

Reduce Risks – Before you start a job:

- get a pre-exposure rabies vaccination and tetanus shot, and stay current;

- have emergency phone numbers handy for your local police, animal control, department of health, state wildlife department, and your doctor;

- vaccinate pets; and

- determine the appropriate protective gear for the situation and know how to use it properly.

While you are working:

- wash your hands thoroughly and often, especially before you eat, drink, or smoke;

- avoid touching your face with your hands;

- keep your gear clean;

- record all animal contact in a daily log;

- be careful when handling a sick animal or one that is behaving oddly;

- remind your doctor about your work with wildlife at every visit;

If you have been bitten or scratched, or are sick, consult your doctor. Safely dispose of animals and contaminated materials.

When you are done for the day clean your gear and truck. Remove work clothing and wash them separately from other clothing. Shower after work.

|

How people can contract diseases |

Precautions for WCOs |

|

Bites or scratches

Boldface type indicates a common way |

Mammal bites or scratches

Mosquito or tick bites

Flea bites

|

|

Inhalation

|

|

|

Transfer of disease agent into mouth, eyes, or nose by dirty hand or object

|

The hand, glove, or object is contaminated with the disease agent (e.g., virus, bacterium, parasite eggs), which usually is too small to be seen with the naked eye.

· Wear a proper respirator, disposable clothing, rubber gloves · Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water, especially before eating, drinking, or smoking · Avoid contact between hands and face |

|

Disease-causing agent enters through wound

|

· Protect wounds and broken skin with bandages if practical · Wear gloves or clothing that covers wound · Check wounds and keep them clean |

|

Ingestion of contaminated food

|

· Wash your hands thoroughly after outdoor activities and especially before eating, drinking, or smoking · Cook meat thoroughly · Filter water when necessary |

|

Handling infected animal

|

· Wear gloves · Minimize contact with mangy animal by using restraining devices · Minimize contact with contaminated clothing and equipment · Dry clothing at high heat to kill any mites |

Common Zoonotic Diseases

Because you work with wildlife, you need to know what diseases these animals can cause in humans. Diseases contracted from wildlife can cause severe sickness and even death. By understanding how wildlife diseases are transmitted to humans, the symptoms they cause, and how to avoid exposure, you can protect your health, your coworkers, and the health of your customers and even the wildlife species you are working with.

Diseases pass from animals to people in many ways. Some of the most common methods of transmission are described below.

Fecal-oral transmission — Pathogens often live in animal feces. Fecal-oral transmission occurs when a person inadvertently ingests animal feces, usually by transferring it from his or her hands to the mouth. For example, if a wildlife operator cleans a trap contaminated with animal feces and does not wash his or her hands before eating, disease transmission can occur. Regular hand washing, especially before eating and after using the bathroom, is very important.

Respiratory transmission — Disease-causing organisms are frequently released into the air when the feces, bedding, or carcass of an infected animal are disturbed. People inhaling these particles can contract the disease. For example, respiratory transmission can occur when a wildlife operator is working in an old chicken house thick with starling droppings. Movement in and around the droppings may kick up dust particles and cause disease. Using a respirator in high-risk situations can help prevent this type of disease transmission.

Direct contact transmission —Humans can sometimes contract diseases from wildlife simply by handling animals or by touching tissues or fluids from infected animals. In these cases, the disease-causing organisms may live on the outside of the animal. To protect yourself, always wear gloves when working. Keep skin covered that may come in contact with animals when handling animals or their tissues and fluids. Wash well after contact with any animal.

Penetrating wound transmission — Organisms need a direct entrance into the human body to cause disease. A wound that penetrates the skin can provide the ideal opening. Wildlife managers may contract these diseases through an animal bite, scratch, or other injury that breaks the skin. Certain vaccinations will help protect you from many diseases transmitted through an open wound.

Vector-borne diseases — A disease vector is a living organism that carries a disease. Humans usually contract vector-borne diseases through the bite of an infected vector. Common vectors of wildlife-related diseases include mosquitoes and ticks. Insect and tick repellents, along with daily checks for ticks, will help protect against this type of transmission. Fleas are vectors of plague, a bacterial disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control, an average of about 7 cases of plague are diagnosed per year in the southwestern US (northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, southern Colorado, California, southern Oregon, and far western Nevada).

Vaccines are available to prevent or reduce the severity of some diseases. People who work with wildlife should consider receiving vaccines for rabies and tetanus. Your doctor may also suggest routine examinations to monitor for some diseases.

Diseases, Based on Transmission

The following discussion describes some diseases you may encounter in your work. They are organized according to their method of transmission. Pay close attention to the symptoms of each condition and ways to avoid exposure.

Fecal-Oral Transmission

Diseases spread through fecal-oral transmission include larva migrans, campylobacteriosis, cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, and salmonellosis.

Larva Migrans (Roundworm and Hookworm Infection)

Larva migrans, or “creeping eruption,” occurs when the larvae of animal roundworms and hookworms travel through the tissues of certain species. The type of illness that occurs depends on which tissues the larvae wander through. The adult worms live in the intestines of a wide range of domestic and wild animals. When infected animals defecate, they pass the eggs of the parasite in their feces. Humans and other animals can acquire roundworm larvae if they touch the feces or items (soil or traps) contaminated by the feces and transfer the eggs to their mouth. Hookworm larvae can enter directly through the skin. The eggs hatch into larvae and mature in the intestinal tract of animals (Figure 3). However, in humans the larvae never mature. Instead, they move through the body and cause harm. Once deposited in the environment, roundworm eggs may survive for months or even years.

Figure 3. Ascarid worms passed by a child.

Photo by James Gathany of the CDC.

Baylisascaris procyonis (causative agent of raccoon roundworm, a type of nematode) is one of the most important wildlife-related species of roundworm. It is a parasite of raccoons, but it may also infect other wildlife, domestic animals, and people. When ingested, B. procyonis eggs hatch, and the larvae migrate aggressively to the eyes, brain, liver, lungs, and other tissues. Larvae have been found in nearly every tissue and organ system. The severity of the disease in a human depends on the number, location, and activity of the roundworm larvae. A mild infection may not produce any symptoms at all. However, if a number of the larvae invade certain parts of the nervous system, infection can cause death or permanent neurological problems.

Doctors use anti-parasitic drugs to treat larva migrans infections. Good hygiene is key to preventing their spread. Anyone who may have been exposed to this disease should seek medical help right away.

Campylobacteriosis

Campylobacteriosis is an infection caused by bacteria called Campylobacter. It affects the intestinal tract and, in rare cases, the bloodstream. Anyone can get a Campylobacter infection. Wildlife operators are at particular risk because they handle animals on a regular basis.

Many animals, most often poultry and cattle, carry Campylobacter in their intestines. Rodents and birds are the wildlife most likely to be sources of human infection. The feces of these animals may contaminate meat products, water supplies, milk, and other foods. People contract campylobacteriosis by eating or drinking contaminated food or water. They also may accidentally swallow the bacteria if they did not wash their hands after touching animal feces.

Campylobacteriosis may cause mild or severe diarrhea, often with fever and traces of blood in the feces. Symptoms usually appear 2 to 5 days after exposure. Infected people continue to pass the bacteria in their feces for a few days to a week or more.

Most people infected with Campylobacter recover without treatment. Antibiotics are useful to treat severe cases or to shorten the carrier phase.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis is a disease caused by Cryptosporidium parvum. This parasite lives in the digestive systems of infected animals and humans. It can infect any pet or farm animal and many wild animals, including birds, fish, and reptiles. When infected animals or humans defecate, they pass Cryptosporidium oocysts (egg-like forms of the parasite) in their feces.

People or animals contract the disease when they swallow the oocysts. This can occur after touching feces from infected humans or animals or after handling objects contaminated with infected feces. Unwashed hands can then transfer the oocysts to the mouth. People who work and play outdoors and/or drink unfiltered stream, river, or lake water can become infected.

The most common symptoms of cryptosporidiosis are watery diarrhea and stomach cramps. Vomiting and low-grade fever may also occur. Symptoms may come and go. They generally last 2 weeks but may continue for a month. Many people do not have any symptoms.

Illness may occur about 2 to 10 days after a person swallows the oocysts. If you think you may have cryptosporidiosis, see your physician right away. People with healthy immune systems usually get well without treatment. People with decreased immunity are at risk for severe disease and death. Currently, no medications have proven effective.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis is an intestinal illness caused by a microscopic parasite called Giardia lamblia. It can infect most animals. Giardia parasites often are associated with beavers and other wild or domestic animals, but humans may be the main reservoir; a reservoir carries but is not affected by the disease. Anyone can get giardiasis.

Giardia is found in the feces of infected people (with or without symptoms) and wild and domestic animals. Giardia parasites spread mainly through person-to-person transmission due to poor hand washing habits. In addition, feces from an infected person or animal may contaminate water or food.

People who ingest Giardia organisms may experience mild or severe diarrhea or, in some instances, no symptoms at all. Fever is rarely present. Occasionally, some people will have chronic diarrhea over several weeks or months, with significant weight loss. Symptoms may appear from 3 to 25 days after exposure but usually within 10 days.

Doctors may prescribe medicine to treat giardiasis. Some people recover without treatment.

Salmonellosis

Salmonellosis is a disease caused by Salmonella bacteria. It usually affects the intestinal tract and occasionally the bloodstream. Salmonella bacteria live in the feces of infected animals or people. They may also contaminate raw animal products including chicken meat, eggs, and unpasteurized milk and cheese.

Salmonella can spread in many ways. A wildlife operator may ingest the bacteria if he or she has direct contact with feces from an infected animal or person and then transfers the bacteria from the hands to the mouth. People also can contract the disease by eating contaminated food (particularly undercooked eggs and poultry) or drinking contaminated water. Once infected, people can spread the bacteria by not washing their hands after using the bathroom.

The most common symptoms are mild or severe diarrhea, fever, stomach pain, headache, and occasionally vomiting. Symptoms generally appear 1 to 3 days after exposure. Once infected, a person may carry the Salmonella bacteria for several days to several weeks. A few infected people carry the bacteria for a year or longer.

Most people with salmonellosis will recover without treatment. Antibiotics and antidiarrheal drugs usually are not recommended.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is caused by a protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii. The most common mode of infection in humans is hand contact with the mouth after handling contaminated objects, or placing contaminated objects directly into the mouth.

Usually, the disease is mild and often is mistaken for a simple cold or viral infection. Most people who are infected never realize it; often flu-like symptoms occur. Common symptoms in adults include swollen lymph nodes, mild fevers, muscle aches, headaches, lethargy, confusion, and pain that last for a few days to several weeks. Very few people show advanced symptoms because the immune system usually keeps the parasite from causing illness. People with compromised immune systems are at greater risk for developing a much more severe infection, and severe infections may result in brain damage or death.

A pregnant woman can transfer the disease to her fetus, but it usually does not cause problems. The worst-case scenarios are miscarriages or serious birth defects.

Cats acquire the Toxoplasma parasite by eating infected wild animals or raw meat. Most mammals can be infected with this parasite. The eggs take about 2 days to become infective. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, infected cats only shed the eggs for 1 to 2 weeks, right after their first exposure to the parasite. As with humans, cats rarely have symptoms when first infected, so most people do not know if a cat has been exposed. No reliable tests are available to determine if a cat is passing Toxoplasma in its feces.

Treatment often is not needed in an otherwise healthy person, unless a woman is pregnant. Symptoms usually disappear within a few weeks. Drugs are available to treat pregnant women or people with weakened immune systems who have toxoplasmosis. Tests are available to determine if a fetus is infected; medication may prevent or reduce the severity of the effects of the infection in a fetus.

Even WCOs who never have a job involving cats can encounter toxoplasmosis. Cats frequent some of the same areas as wild animals. Use standard precautions to avoid contact with cat feces.

Preventing Fecal-Oral Transmission

Good hygiene, especially frequent hand washing (Figure 4), is the key to protecting yourself from diseases spread by fecal-oral transmission.

Figure 4. Regular hand washing can prevent most fecal-orally transmitted diseases. Photo in public domain.

The following are important ways to prevent this type of disease transmission.

- If possible, wear disposable or washable gloves when handling animals or objects contaminated with their feces.

- Wash your hands with soap and water:

- after handling animal feces or objects contaminated with animal feces,

- after direct contact with soil,

- after using the toilet, and

- before eating or handling food.

Avoid water or food that may be contaminated. Do not drink water directly from streams, lakes, springs, or any unknown source. If you suspect your drinking water is unsafe, boil it for 1 minute before using.

Prompt removal and destruction of raccoon feces will reduce the risk of raccoon roundworm exposure to humans. Raccoons use latrines, and typically defecate at the base of trees, on fallen logs, large rocks, and wood piles, and in barns and other outbuildings. Feces of raccoons also may be found in attics, fireplaces, garages, decks, rooftops, haylofts, and compost piles

Disinfect or torch cages, traps, and other items contaminated with animal feces. This will prevent the spread of disease from one animal to another. You can use a commercial disinfectant or prepare a solution of 1 ½ cups bleach to 1 gallon of water.

If you contract a fecal-orally transmitted disease, wash your hands often to avoid spreading the disease to your coworkers or family.

Respiratory Transmission

Diseases spread through respiratory transmission (inhalation) include hantavirus, histoplasmosis, and psittacosis. Always wear a respirator when you suspect pathogens are in the air.

Hantavirus

Hantaviruses cause rare but extremely serious respiratory illness. The first US cases occurred in the Southwest in 1993. Although still most common in the Southwest, hantaviruses occasionally occur in other parts of the country. Anyone exposed to rodents or rodent-infested areas is at risk for contracting hantavirus disease. This includes many wildlife operators. Infected wild rodents, mainly deer mice (Figure 5), carry the disease. White-footed mice, rice rats, and cotton rats also carry the virus.

Figure 5. Deer mice are common carriers of Hantavirus.

Photo by CDC.

The virus is transmitted in the animal’s urine, saliva, and droppings. It gets in the air as mist or dust when fresh droppings (less than 3 days old) are disturbed. Hantaviruses spread to humans when people breathe the contaminated mist or dust. You also can contract the disease by handling rodents or by touching your nose or mouth after handling contaminated materials. In addition, the bite of an infected rodent can spread the virus. There is no evidence that cats or dogs transmit the disease to humans. You cannot get hantavirus from another person.

Early symptoms include fever (101°F to 104°F) and muscle aches. Hantavirus also may cause headaches, coughing, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and stomach pain. The main symptom of this disease is difficulty breathing due to fluid buildup in the lungs. This can progress rapidly to respiratory failure (the inability to breathe).

Symptoms usually start about 2 weeks after exposure. However, the incubation period can be as short as 3 days or as long as 6 weeks.

Currently, there is no specific treatment for hantavirus disease. Early hospital care is the only known therapy. If you think you may have hantavirus disease, contact your doctor immediately.

Hantavirus Specifics

The CDC recommends these steps to safely dispose of dead rodents:

- Thoroughly spray dead rodents with disinfectant.

- Place each rodent in a plastic bag with enough disinfectant to thoroughly wet the carcass. Tightly seal the bag and place it into a second plastic bag.

- To clean up a heavy rodent infestation, burn or bury the bag, if possible. Otherwise, contact your local health department about other appropriate disposal methods.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is an infection caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. The symptoms vary greatly, but this disease mainly affects the lungs. It rarely invades other parts of the body.

Anyone can get histoplasmosis. Positive skin tests appear in as many as 80% of people living in some areas of the eastern and central US. However, most of these people never show any symptoms. Often called “cave sickness,” histoplasmosis sometimes afflicts people who explore caves for a hobby. Bats, dogs, cats, rats, skunks, opossums, foxes, and other animals also can get histoplasmosis.

The histoplasmosis fungus grows in soil enriched with bat or bird (especially chicken) droppings that are 3 or more years old. These soils may exist around old chicken houses, near roosts of starlings and blackbirds, in decaying trees, in caves, and in other areas where bats live, including indoors in attics (Figure 6). The fungus produces spores that get into the air if the contaminated soil is disturbed. Inhaling these spores causes infection. You cannot get histoplasmosis directly from another person or an animal.

Figure 6. In an attic, the fungus Histoplasma caspulatum (1) may be present in bat droppings. Image by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Most people with histoplasmosis have no symptoms. For those who do get sick, illness can vary from a mild respiratory disease to a serious illness that strikes the whole body. Most people have the mild respiratory form of the illness. This may include fever, chest pains, weakness, and sometimes a cough. The most serious forms of the disease can lead to death if not treated. If symptoms appear, they usually do so within 5 to 18 days after exposure. Ten days is average.

Treatment usually is not appropriate for histoplasmosis. Most people will get better without treatment. However, antibiotics may be necessary for severe cases of the disease. Once you contract histoplasmosis, you usually do not get it again.

Psittacosis

Psittacosis, also known as parrot fever, is caused by the bacteria Chlamydophila psittaci. Most human cases of psittacosis result from exposure to infected pet birds like cockatiels and parrots. However, the bacterium that causes psittacosis has been identified in more than 100 species of birds. Wildlife operators are most likely to be exposed to psittacosis when handling feral pigeons or other wild birds.

People usually become infected when they inhale disease-causing bacteria in aerosol droplets from dried feces or respiratory secretions of infected birds. Exposure can also occur if a person handles the feathers or tissues of sick birds. In addition, sheep, goats, and cattle may become infected and transmit the disease to people.

Symptoms typically include sudden fever, chills, headache, cough, difficulty breathing, and chest tightness. Pneumonia and other serious problems also may result. Some people who are exposed do not develop any symptoms. Death from psittacosis is very rare with standard antibiotic treatment. Tell your doctor of any exposure to birds infected with the Chlamydophila psittaci organisms — and to birds in general — if you develop any of the above symptoms. To prevent infection:

- Wear gloves when handling birds, especially those sick or known to be infected.

- Wear a snugly fitting mask (N95 or higher rating) to prevent inhaling dust from fecal and respiratory droppings. This is especially important when cleaning areas where visible amounts of these materials from infected birds have accumulated. Alternatively, dampen the area with water and detergent before cleaning.

- Wash your hands whenever they are dirty, before eating, and after using the bathroom.

Preventing Respiratory Transmission

It is not practical to test or decontaminate all areas where hantaviruses or the histoplasmosis fungus may occur. However, you can take the following steps to minimize your exposure to these and other diseases contracted by respiratory transmission.

- When possible, avoid areas where diseases may occur.

- Do not stir up or breathe dust. If you are going into a closed building, garage, or basement, open it and let it air out for at least 1 hour before working inside. Gently spray down areas with disinfectant, including soil that may be contaminated with animal feces or urine. You can use a commercial disinfectant or prepare a solution of 1 ½ cups bleach to 1 gallon of water. Use a spray bottle to mist the area (Figure 7). A hard spray will just stir up more dust. Be sure that all surfaces and soils are thoroughly wet before cleaning them up.

- If you work in an area where bird or bat droppings have accumulated for several years, wear disposable clothing and a respirator approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). It must be able to filter out particles larger than 1 micron in diameter.

- Disinfect all used traps or replace them. If you must work in high-risk areas, wear rubber gloves. Gloves are especially important when you handle animals, traps, or other exposed items. Before removing the gloves, wash your hands in disinfectant and then in soap and water. Then, remove the gloves and thoroughly wash your hands with soap and water.

Figure 7. To minimize exposure to airborne diseases, clean and disinfect infested areas.

Direct Contact Transmission

Diseases spread through direct contact transmission include brucellosis, leptospirosis, and tularemia.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is a disease that can spread from infected animals to humans through broken skin. Contact with tissues, fluids, and aborted fetuses of infected animals is most dangerous. Brucellosis is caused by the Brucella bacteria. The disease is under control in most farm animals in the US. However, there are still pockets of infection. Wildlife such as bison, elk, caribou, feral pigs, and some species of deer may still carry the disease. Brucellosis also can occur in some dog kennels.

Humans get brucellosis from animals, not from other people. Brucella can enter the body through the mouth, nose, and eyes, and through cuts or breaks in the skin. People usually get brucellosis by handling the tissues, blood, urine, vaginal discharges, aborted fetuses, and placentas of infected animals. Drinking unpasteurized milk or eating products made from raw milk (butter, whipped cream, and soft cheeses) from infected animals also may lead to infection.

Brucellosis causes a flulike illness with fever, chills, headaches, body aches, and weakness. The fever may fluctuate over a 24-hour period. Other symptoms may include weight loss, lack of appetite, and prolonged fatigue. Symptoms commonly appear 1 to 2 months after exposure.

Early diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics is important. Left untreated, brucellosis may periodically cause fever and fatigue and can lead to arthritis. Sometimes it is necessary to treat a person more than once to eliminate the organism.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a disease caused by Leptospira bacteria. It can infect a wide range of domestic and wild animals such as dogs, raccoons, rodents, deer, squirrels, foxes, skunks, opossums, and marine mammals. Infected animals may not show any symptoms, but will shed the organism in their urine. It occurs more often in people who work with animals or who have direct contact with streams, ponds, or lakes contaminated with animal urine.

Most people get leptospirosis by contact (through a break in the skin or inadvertent ingestion) with soil, water, or vegetation soiled with the urine of infected animals. Leptospirosis is not normally transmitted from person to person.

People exposed to leptospirosis may have severe symptoms or no symptoms at all. Symptoms include a sudden fever, chills, headaches, body aches, and fatigue. The disease also can affect the liver, kidneys, or nervous system. Leptospirosis may last for several weeks. It is rarely fatal. Symptoms appear from 4 to 19 days after exposure.

Doctors may prescribe antibiotics to treat leptospirosis. People who suspect they have contracted the disease should seek treatment promptly.

Tularemia

Many different animals may carry tularemia, caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. Common carriers include rabbits, ground squirrels, muskrats, mice, and beavers. Hunters, especially rabbit hunters, may be at a higher risk of acquiring this disease.

Ticks also can carry tularemia. In fact, bites from infected ticks account for most cases. Tularemia bacteria can be found in many species of ticks, especially the lone star tick, the Rocky Mountain wood tick, and the American dog tick. Tularemia occurs year-round but is most common in the summer when people are outdoors and ticks are abundant. Many cases also have occurred during the fall and winter rabbit-hunting seasons.

Tularemia also may be aerosolized and inhaled, usually when mowing or yardwork disturbs the habitat of an infected animal.

Risk factors for contracting tularemia include:

- being bitten by an infected tick or deer fly;

- exposing skin or mucous membranes when handling, skinning, or butchering infected animals; and

- eating contaminated, undercooked meat or drinking contaminated water.

To avoid contracting tularemia:

- avoid the bites of arthropods and wear insect repellent in bug-infested areas;

- use rubber gloves when skinning or handling animals, especially rabbits;

- do not drink, bathe, swim, or work in untreated water where wild animals are known to be infected; and

- cook the meat of wild rabbits and rodents thoroughly before eating it.

Symptoms can vary depending on how a person was exposed to tularemia. Symptoms may include a sudden onset of fever, chills, headache, sore muscles, and fatigue. Many people who are exposed to tularemia via a tick bite develop an ulcer at the site of the bite. The severity of the illness varies but may be fatal if left untreated.

Preventing Direct Contact

Disease Transmission

The best ways to prevent direct contact transmission of diseases are:

- use good sanitation and

- avoid risky situations.

Risky situations may include handling afterbirths and drinking or touching water contaminated with animal urine. Be sure to wear boots and gloves when working with animals or in potentially infected areas. Wash your hands often.

Wild birds and mammals also may be infested with mites and/or lice. While these organisms prefer animal hosts, they can transfer to humans through direct contact. If mites and lice get on humans, they can cause itching and general irritation. Always wear gloves and wash well. Check with a veterinarian for suitable pesticides to rid animals of mites and lice.

Penetrating Wound Transmission

Diseases that spread through penetrating wound transmission include rabies and tetanus.

Rabies

Rabies is a disease that affects the nervous system of animals and humans. It is caused by a virus present in the saliva and brain/spinal cord of infected animals. The virus usually is transmitted to other animals or humans either by the bite of a rabid animal or by contact with infected saliva.

Only mammals are susceptible to rabies. The disease mainly affects bats and furbearers in the US, especially skunks, raccoons, foxes, and coyotes (Figure 8). Rabbits and most rodents rarely are diagnosed with the disease.

Figure 8. In the US, the animals that get rabies the most are raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats. Photos by CDC.

Symptoms of rabies you may see in wild animals include:

- unprovoked aggression – or “furious rabies” in which some animals attack anything that moves or inanimate objects);

- unusual friendliness – or “dumb rabies” in which normally secretive animals approach people and nocturnal animals become active during the day, (although some daytime activity is normal, especially when nocturnal animals are feeding their young);

- stumbling, falling, appearing disoriented or uncoordinated, or wandering aimlessly;

- paralysis, often beginning in the hind legs or throat (paralysis of the throat muscles can cause the animal to drool, choke, and froth at the mouth);

- vocalization ranging from chattering to shrill screams;

- sore feet in which raccoons walk as if they are on hot pavement

Rabid skunks, raccoons, foxes, and dogs usually display furious rabies. Rabid bats often display dumb rabies and may be found on the ground, unable to fly. “Grounded” bats pose a risk to children and pets. In domestic animals, rabies should be suspected if there is a sudden change in disposition, failure to eat or drink, if the animal becomes paralyzed, or if it runs into objects. Cats, dogs, sheep, goats, cattle, and horses can contract rabies.

You cannot tell whether an animal is rabid just by its behavior. Other diseases, such as distemper and toxoplasmosis, can cause similar symptoms. An animal that has been poisoned by lead, mercury, or antifreeze also may act rabid. The only way to prove that an animal is rabid is to have its brain tissue tested in a laboratory.

The period of time between when the virus enters the body and when it reaches the brain and produces symptoms is called the incubation period. In humans, this interval varies from 10 days to a year or more. The average incubation period is 14 to 60 days. The length of incubation depends on the location and severity of the bite or wound. Bites on the head and neck usually produce symptoms more rapidly because these areas are closer to the brain.

A person infected with rabies may have difficulty swallowing or suffer from general tiredness, spasms of the breathing muscles, anxiety, depression, irritability, and delirium. The infected person may eventually lapse into a coma. Death is most often due to respiratory paralysis (inability to breathe).

If an animal known or suspected to be rabid bites a human or a domestic animal, that person or animal should receive anti-rabies vaccinations promptly. Quick action is critical because treatment is useless if administered after symptoms appear. Once symptoms develop, the disease is nearly always fatal.

If the biting animal is a dog, cat, or ferret and you can catch it safely, determine from the owner if the animal is up-to-date on its rabies vaccinations. Then call the local health department to report the bite and inquire about quarantine guidelines. If the animal appears to be normal at the end of the quarantine period, it is determined to be negative for rabies. The injured person does not need rabies treatment. For animals other than dogs, cats, and ferrets, especially wild carnivores and bats, you cannot rely on an observation period. Instead, kill the animal (being careful not to damage the head, as brain tissue is needed for the rabies test) and report the bite to the local health department. Follow the advice of the health department regarding submission of the animal for rabies testing.

Even if the animal is not available for testing, call the local health department and report the bite. The health department will determine if the bitten human or domestic animal needs to receive post-exposure treatment for rabies. Rabies treatment is recommended only when someone has been exposed to a known or suspect rabid animal.

A person may be exposed to rabies by any bite, scratch, or other circumstance where saliva or central nervous system (CNS) tissue from a potentially rabid animal enters an open, fresh wound or comes in contact with a mucous membrane by entering the eye, mouth, or nose. Touching or handling a potentially rabid animal or another animal or inanimate object that had contact with a rabid animal does not constitute an exposure unless wet saliva or CNS material from the potentially rabid animal entered a fresh, open wound or had contact with a mucous membrane. It is also possible to inhale the virus in the air, as in a bat-infested cave, or aerosolized by gunshots to the head of a rabid animal.

Due to the nature of bat bites (small, sometimes unnoticed), evaluating exposures to bats is different than evaluating exposures to terrestrial mammals. Anyone who has had direct contact with a bat and cannot rule out a bite or has been in a room where the level of contact with a bat is uncertain (such as when a bat is discovered in a room with a sleeping adult or unattended child, an intellectually impaired person, or a person who is intoxicated) should be considered exposed.

Wildlife operators and others who handle animals regularly should receive an initial series of rabies pre-exposure vaccines, followed by a blood test every 2 years to check titer, the level of anti-rabies antibodies. If the blood test shows that there is a lower than desired number of antibodies, a single booster vaccination is necessary. Anyone who has had the pre-exposure vaccinations and is exposed to a rabid animal should immediately call the health department and report the bite.

Tetanus

Tetanus, often called lockjaw, is a bacterial disease that affects the nervous system. It is caused by a naturally occurring bacterium, Clostridium tetani, which lives in soil contaminated with manure. Tetanus bacteria enter the body through a wound (animal bite or cut) contaminated with the bacteria. The disease does not spread from person to person. Thanks to widespread immunization, tetanus is now rare in the US.

It is far less likely that those who are vaccinated against tetanus will get the disease. Wildlife operators and those who may experience wounds and who contact soil regularly are at greatest risk.

A common first sign of tetanus is muscular stiffness in the jaw. Next, stiffness of the neck, difficulty swallowing, rigidity of abdominal muscles, and spasms may develop. The incubation period is usually 10 days but may range from 3 days to 3 weeks. Recovery from tetanus may not give immunity; a person who has had tetanus can get it again.

To protect yourself from tetanus, be sure to thoroughly clean all wounds. If you have not had a tetanus toxoid booster in the previous 10 years, get a single booster on the day of injury. In addition, if you sustain a major wound and the wound becomes contaminated, or you are wounded by a dirty or rusty object, you may need a booster vaccine.

The tetanus toxoid vaccine usually will prevent the development of tetanus. The CDC strongly recommends that everyone, particularly people who work outdoors, get a tetanus booster every 10 years.

Preventing Penetrating Wound Transmission

The single most important way to prevent rabies and tetanus is to maintain a high level of immunization. Vaccines are available for both diseases. Anyone who handles animals regularly, especially wild animals, should be vaccinated for rabies. Have pets and other domestic animals vaccinated regularly. Try to avoid risky situations where animal bites or injuries are likely. If you do suffer a penetrating wound, thoroughly clean it and contact your doctor right away.

Vector-borne Diseases

A disease vector is a living organism that carries a disease. Common vectors of wildlife-related diseases include mosquitoes and ticks. The following are several common vector-borne diseases often associated with wildlife and areas where WCOs may work. They are organized according to the vector that transmits them to humans.

Mosquito-borne Diseases

These infections generally occur during warm weather when mosquitoes are active. Symptoms of the different viral infections are similar but differ in severity. Most infections do not cause symptoms. Mild cases may cause only a slight fever or headache. Severe infections can cause headache, high fever, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, paralysis, or death. Symptoms usually appear 5 to 15 days after exposure.

No specific treatment is available for mosquito-borne disease infections in humans. However, doctors usually will try to relieve the symptoms of the illness.

West Nile Virus

Most infections of West Nile virus are mild. The most vulnerable groups include the elderly and those with compromised immune systems. The most common mode of infection in humans is through a mosquito bite (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Mosquitoes are vectors of West Nile virus. Photo by Jim Kalisch.

West Nile virus lives in the salivary glands of mosquitoes. It causes a variety of symptoms that usually appear in 3 to 14 days. The most common symptoms are mild and flu-like, including fever, rash, lethargy, and loss of appetite. A small percentage of people develop an infection of the central nervous system that may cause encephalitis and meningitis. Rarely, West Nile virus causes paralysis or death.

The disease was first reported in the eastern US in the summer of 1999 and it had spread across the US by 2004. Birds likely spread the disease during migration. To date, 20% to 30% of people infected with West Nile virus have become ill.

West Nile virus affects more than 70 species of domestic and wild birds (especially American crows, jays, hawks, and owls) and mammals (especially people and horses). West Nile virus has significantly affected populations of some rare and endangered birds. The virus does not appear to cause serious illness in dogs or cats. It has been found in bats, chipmunks, raccoons, skunks, squirrels, domestic rabbits, mountain goats, and reindeer. In 2002, West Nile virus was identified as a cause of death of American alligators.

Normally, the virus cycles between mosquitoes and birds. When an infected mosquito bites a bird, it transmits the virus to the bird. The virus circulates in the bird’s blood for a few days. Uninfected mosquitoes that bite an infected bird may pick up the virus. The virus may replicate in the mosquito’s body and be transmitted to another animal by another bite. The virus does not replicate effectively in mammals, so an uninfected mosquito biting an infected mammal probably cannot pick up the virus. Thus, mammals are currently considered dead-end hosts for West Nile virus.

Treatment for people infected with West Nile virus often includes general support. No vaccine exists at present, but medications and a vaccine are in development.

Anyone can get a mosquito-borne infection. However, people who work outdoors, especially near water, are most susceptible. Fortunately, only a few types of mosquitoes are able to spread the disease. Of these, only a small number actually carry the viruses.

Preventing Mosquito-borne Diseases

- Wear a long-sleeved shirt and long pants.

- Use insect repellents when working outdoors in mosquito-infested areas.

- Avoid working at dawn and dusk when mosquitoes are most active.

Insect repellents with the chemical DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) or picaridin usually work well. Oil of lemon eucalyptus, a plant-based repellent, is also effective. For more information on avoiding mosquitoes, contact your state Department of Health.

Tick-borne Diseases

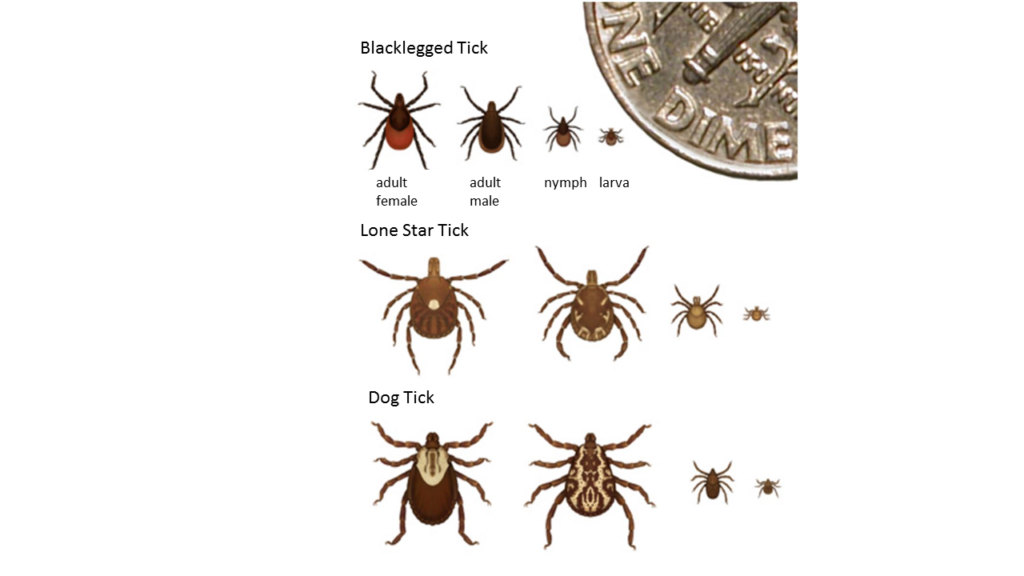

Important tick-borne diseases include ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Common vectors are the dog tick, black-legged (deer) tick, and lone star tick (Figure 10).

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis is caused by Ehrlichia bacteria, which can infect 2 different types of white blood cells. Ehrlichiosis affects both humans and animals. People who spend time outdoors in tick-infested areas are at greatest risk for exposure.

Ehrlichia bacteria are transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected tick, usually the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) and, less frequently, the black-legged (deer) tick (Ixodes scapularis). Ehrlichiosis cannot spread from person to person.

Figure 10. Common vectors of tick-borne diseases, showing relative sizes. Image by CDC.

The most common symptoms are fever, chills, muscle aches, weakness, and headache. Patients also may experience confusion, nausea, vomiting, and joint pain. Unlike Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever, a rash is not common among adults. Infection usually produces mild to moderately severe illness, with high fever and headache. Rarely is ehrlichiosis fatal.

The incubation period is usually 5 to 21 days after exposure to an infected tick. However, not every exposure results in infection. Tetracycline antibiotics usually are very effective for treating ehrlichiosis.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease is an inflammatory disorder caused by a type of bacteria called a spirochete. Lyme disease spreads through black-legged (deer) ticks. Lone star ticks also may be vectors of Lyme disease. Black-legged ticks live on deer, rodents, and other wildlife. Humans, dogs, and wildlife can contract Lyme disease through the bite of an infected tick. However, the tick typically needs to be attached to the body for 24 hours or longer for the bacteria to transfer from the tick to the host. You cannot get Lyme disease from animals or other people.

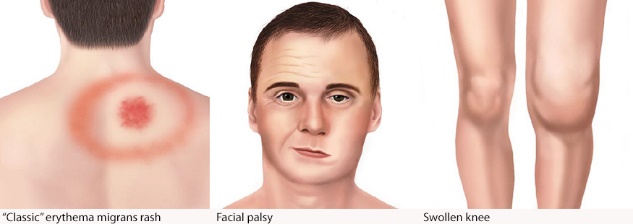

In most people, the first symptom is a skin lesion that forms at the site of the tick bite. This may appear within 2 to 32 days (usually within 1 to 2 weeks). The lesion is red and slowly gets bigger, usually with a bulls-eye or target appearance (Figure 11). Flu-like symptoms such as fatigue, fever, headaches, stiff neck, and muscle or joint pain often accompany the initial lesion. These symptoms may last several weeks.

Figure 11. Symptoms of Lyme disease. Image by CDC.

In some cases, these first symptoms may not occur. If this happens and the disease is not treated, a second set of symptoms may occur.

These include nervous disorders, facial palsy (droop on one of both sides of the face), heart problems, or joint swelling and chronic arthritis. Early treatment with antibiotics will prevent the arthritic and other late stages from developing.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) occurs throughout the US. In some states, the most common vector is the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis). Several other tick species also carry the disease. Dog ticks live on dogs, rodents, and other animals. Humans contract the disease from the bite of an infected tick. The infected tick must remain attached for at least 4 to 6 hours before infection is possible. People may also get RMSF if the blood or feces of an infected tick contaminates broken skin. The disease is not directly transmitted from person to person.

Symptoms usually appear within 2 weeks of the bite of an infected tick. There is a sudden onset of a moderate to high fever. Fatigue, deep muscle pain, severe headaches, chills, and an eye infection often accompany the fever. These symptoms may last for 2 to 3 weeks.

The distinguishing symptom of RMSF is a rash that appears between the 2nd and 5th day of infection. The spots are rose red and may become deep red or purple. The rash appears first on the wrists, forearms, ankles, and bottoms of the feet. It spreads quickly to the back, then to the arms, legs, chest, and abdomen.

Early treatment with antibiotics is most effective against the disease. Currently, there is no vaccine available to prevent RMSF.

Preventing Tick-borne Diseases

The best way to prevent tick-borne diseases is to avoid tick-infested areas, such as tall grass and dense vegetation. Ticks do not jump or fly onto people. They wait on vegetation and attach to hosts that pass by.

When you must work in tick-infested areas, take the following steps to protect yourself from exposure:

- Wear light-colored clothing so that ticks are easier to see and remove.

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and pants. Tuck your pants legs into your socks.

- Apply tick repellents containing DEET to exposed skin and clothing. Use repellents sparingly and avoid prolonged or excessive applications.

- Apply permethrin treatments to clothing, following pesticide label instructions.

- Walk in the center of trails to avoid brushing against vegetation.

- Check body surfaces and clothing during and after being outdoors.

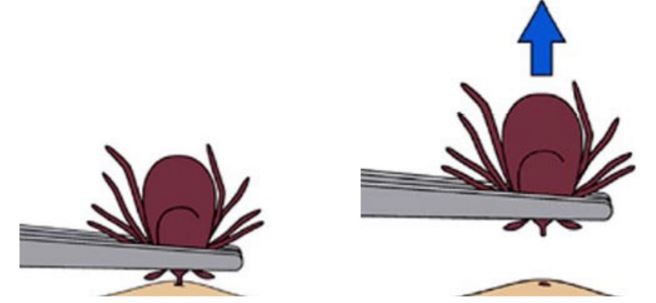

Remove an attached tick as soon as possible. Use tweezers to grab the tick close to the skin and pull it straight out (Figure 12). Do not squeeze the tick’s body when removing it. Avoid twisting or jerking motions that may break off the mouthparts in the skin. Mouthparts left in the wound will not transmit the disease, but they may cause a mild infection. Do not handle the tick with bare hands. Some tick-borne diseases can enter the body through a break in the skin. After removing the tick, wash the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol or soap and water.

Figure 12. Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist or jerk the tick; this can cause the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin. If this happens, remove the mouth-parts with clean tweezers. If you are unable to remove mouth-parts easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal. Text and images by CDC.

You may dispose of the tick by drowning it in alcohol, or flushing it down the drain or toilet. However, consider keeping the tick in case disease symptoms develop later on. Identifying the tick could help in making a diagnosis. If you get sick after being exposed, contact your doctor right away. Be sure to mention your occupation and tick exposure.

The Bottom Line Regarding Diseases

Adopt a healthy lifestyle, be aware of the risks, and wear appropriate protective equipment to protect yourself from zoonotic diseases. Regularly remind your doctor that you work with wildlife and areas laden with fecal contamination. Carry a card in your wallet (Figure 13). This reminder will help your doctor consider other possible diseases if you become ill.

Figure 13. This card can help inform medical personnel that you work with wildlife. Image by the CDC, USGS.

More wildlife diseases safety tips.

To reduce the risk of exposure to wildlife diseases use gloves, a respirator, disposable clothing, restraining devices, and traps.

Tetanus is not a wildlife disease. Protect yourself because of the chance of hurting yourself on a contaminated nail or sharp object that penetrates the skin.

Rabies is a deadly disease. Raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats are commonly infected; approach all wildlife with caution.

Be careful of bites, especially if you use something other than a trap to capture the animal.

Acknowledgments

Reviewed by

- Michael E. Beran, All Animal Control of Northwest Louisiana;

- Kevin Cornwell, Cornwell’s Wildlife Control, LLC; and

- Claudia Paluch, NWCO, Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitator, State of Connecticut.

Study Questions for Wildlife Diseases

Questions for Reflection

- Name 5 ways you can be infected with a zoonotic disease.

- Choose a disease and provide an example for each of the following terms: host, vector, reservoir, and agent. Explain how they relate to the spread of that disease.

- A client says he heard a lot of activity in the attic and wants you to examine it. Explain what you should do before entering the attic.

- You enter a room and notice several brown and black specks scattered around the floor. What would you do and why?

- Describe how you would protect yourself from tick-borne diseases.

Objective Questions

- Match the term to the definition

- host

- reservoir

- vector

- agent

__ carries but is not negatively affected

by the disease

_ negatively affected by the disease

__ the route or transporter of

the infection

__ the entity that causes disease

Diseases normally enter your body through all the following ways EXCEPT

-

- intact skin

- mucous membrane

- injection

- inhalation

- ingestion

- True or False – The trouble with diagnosing zoonotic diseases is that the symptoms often mirror those of the flu.

- What disease is of concern when a client calls with a bat flying in the house?

- rabies

- raccoon roundworm

- mange

- distemper

- To protect yourself from zoonotic diseases and their impact on your health, you should

wear personal protective equipment

avoid contaminated areas

get vaccinated

inform medical personnel you work with wildlife

all of the above

Answers

- b. reservoir, a. host, c. vector, d. agent

- a

- True

- a

- e____________